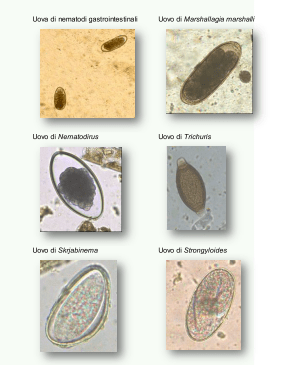

Photo 1: goat gastrointestinal nematode eggs at light microscope

Dairy goat endoparasites

Parasites are living organisms (protozoa, helminths, arthropods) that derive their livelihoods from other species (hosts), with benefit to the parasite and harm to the host. Parasites are defined as pathogens, although they do not always largely harm the host nor necessarily cause their death, since this would also harm the parasites themselves.

Among endoparasites, gastrointestinal nematodes (GIN) are those that worldwide have a high zootechnical and economic importance for bred ruminants and represent the most widespread parasitosis in both goats and sheep.

Gastrointestinal nematodes

Gastrointestinal nematodes (GIN) are a group of parasitic worms that lives in the digestive system of their hosts, by localizing in a specific tract of the gastroenteric system (abomasum, small intestine, or large intestine) and comprises the families Strongyloididae (Strongyloides), Strongylidae (Chabertia, Oesophagostomum) Trichostrongylidae (Trichostrongylus, Ostertagia, Teladorsagia, Cooperia, Marshallagia), Molineidae (Nematodirus), Ancylostomatidae (Bunostomum) and Trichuridae (Trichuris).

Such parasites do not multiply inside the host, they have relatively large sizes (in terms of millimetres, if not centimetres), have relatively long generation times, and do not transmit directly from one animal to another. They have one exogenous development phase (in the environment) and another one endogenous (in the host) that consists of various stages at different localization and physiology, and therefore pathogenesis. They are characterized by a complex antigenic mosaic and evoke a premunition immunity. The result is the tendency to create a kind of balance with the host by an aggregated distribution. GIN infestations are characterized by polyparasitism, with guests usually infested by 3–4 genera, 8 species, at the same time.

Their pathogenic effect is variable; in general, the greatest effects are caused by the larvae during the intramucosal phase. Adult parasites live free in the lumen and feed on food material, they are equipped with a digestive system and have an oral cavity, with or without aggressive structures (e.g. teeth) through which they take the food that can consist of blood, tissues, and chime.

They have separate sexes and show sexual dimorphism; after mating, the female produces eggs that are scattered in the external environment through the faeces of the host at the morula stage or containing a first stage larva (Strongyloides). Eggs, isolated by appropriate parasitological techniques, make it possible to diagnose GIN infestations in in vivo animals (Photo 1).

Biological life cycle

Gastrointestinal nematodes have a direct life cycle. For most GIN species, outside the host, eggs become embryos. Over their development, GIN undergo 4 moulting. During metamorphosis, there are no profound changes from one larval form to the other one and the different development stages are very close morphologically, except for the size and the presence in the adult of the mature genital apparatus. In the environment, L1 hatch from the embryonic eggs and mutate to L2 losing the cuticle. In the next moulting from L2 to L3 the cuticle of the previous stage is preserved instead. L3 larvae sheathed in the L2 cuticle, remain at this stage, also called “stop stage” or “hypobiosis”, until a new host is available and to survive use the reserves stored under the L2 cuticle. The third stage larva is the infesting form.

Photo 3: paleness of the oral mucous membranes following a severe anemic state induced by Haemonchus contortus in an adult goat that died due to massive infection

Photo 4: Anterior end of an adult male specimen of Haemonchus contortus; nematode that is localized in the goat’s abomasum

Photo 5: Oral cavity of an adult male specimen of Haemonchus contortus; we note the triangular denticle that the parasite uses to cut the abomasal mucosa and to take the blood meal.

Photo 6: Posterior end of an adult male specimen of Haemonchus contortus; we note the spicules, structures of the male genital system.

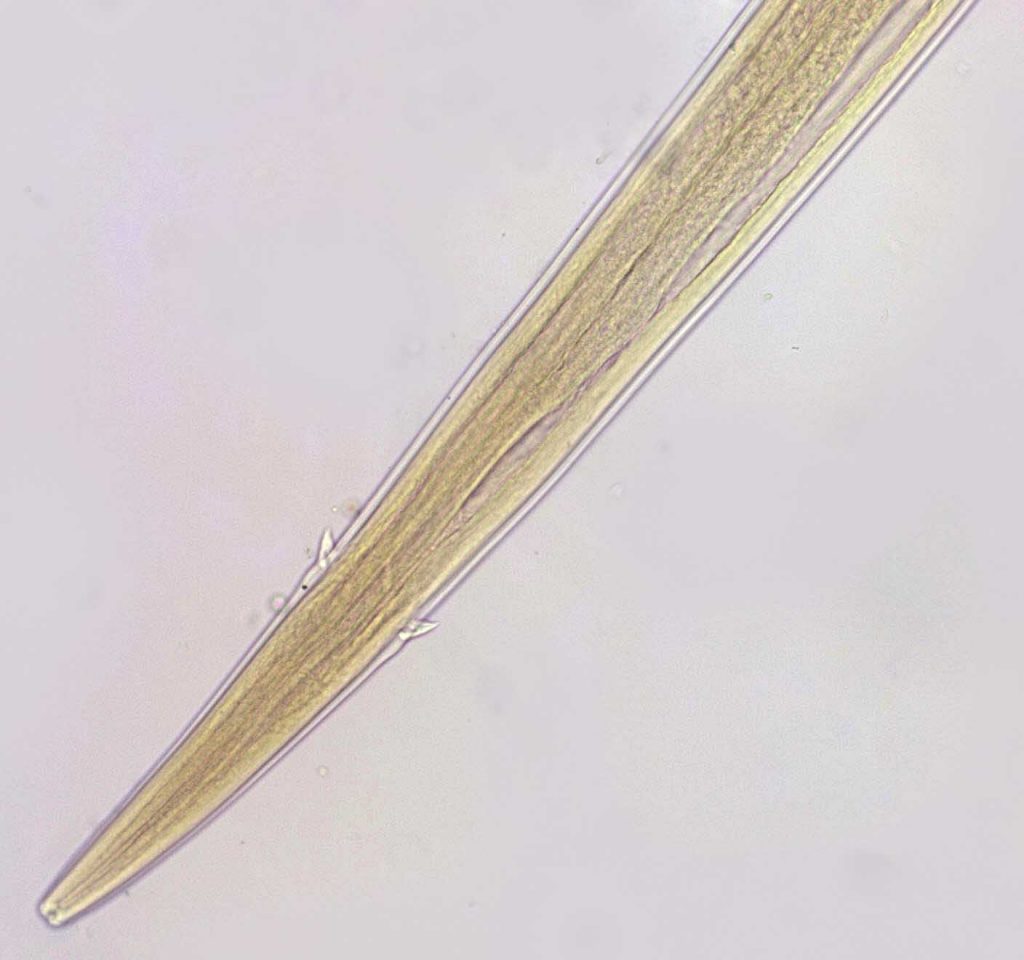

Photo 7: Third stage larva of a gastrointestinal nematode; we note the long caudal end that the larva uses to move around the environment

Gastrointestinal nematodes in the host

Ruminants infest by ingesting infesting parasite stages along with the fodder. Such larvae first penetrate the mucous membrane of the organ and remain there until they have completed their development reaching the fifth stage. Then, they return in the lumen of the abomasum or of the intestine where they become adults, they reproduce, and the elimination of the eggs begins. Third stage larvae of abomasal parasites penetrate the abomasum glands within a few hours from the ingestion and remain there for about 2 or 3 weeks. In this period, the larvae grow, and the glands increase in volume; the mucous membrane is inflamed. The body of the larvae exerts compression on the cells of the parasitized glands that gradually lose their activity and are replaced by undifferentiated cells. Morphological modifications of the mucous membrane are followed by biochemical changes of a magnitude proportional to the number of parasitized glands.

Gastrointestinal nematodes in the environment

The survival of infesting larvae of ruminants’ gastrointestinal nematodes on the pasture varies from a few weeks to a few months depending on the parasite species and the environmental conditions. Infesting larvae can live for a long time on the pasture and in any case, L3 are more resistant than other stages, as they have preserved the lining of the previous stage during the moulting process and are therefore protected by a double sheath.

Environmental temperature, oxygen concentration, and stool moisture are the main factors that act on the hatching rate of GIN eggs. In general, under favourable environmental conditions (high humidity and temperature), the development of L3 takes about 7-10 days. The optimal conditions for the development of the larvae are those in which temperatures are between 18-26°C and 100% relative humidity (RH).

In temperate climate regions, most GIN eggs develop in late spring, summer, and early autumn. Teladorsagia circumcincta is the most important abomasal nematode of goats. At 4°C, 95% of the eggs of T. circumcincta hatch in 3-5 days and the largest number of L3 is formed at a temperature of 16°C, while for the other tricostrongilid nematodes the optimal temperature is 25°C. Above 16°C, larval development occurs faster but the number of larvae of T. circumcincta gradually decreases as mortality increases. In climatic conditions characterized by a particular drought, the larvae find a microclimate sufficient for their survival within the faecal mass or refuging in the soil that constitute real reservoirs, that are gradually abandoned by the larvae to disperse into the environment.

Infesting L3 larvae can make movements on pastures and have been observed up to 40 cm away from the faecal mass. Generally, they are found between 8 and 15 cm from faecal material. They are also able to penetrate the soil, especially if the sandy component is prevalent, up to a depth of 15 cm. The movement of the larvae (L3) on the pasture depends firstly on moisture and secondly on temperature.

The migration of the larvae on the vegetation is regulated by light, humidity, and gravity. On the pasture, at dawn, a large number of larvae migrate to the grass when the humidity is high and the grass is wet, and return to the ground during the day when the humidity is low to avoid dehydration. At dusk, they go back up but to a much lesser extent.

Vertical migration of the larvae can be affected by the type of vegetation composing the pasture; in the presence of fescue larvae can reach 40 cm in height, whereas up to 28 cm or 20 cm if the pasture consists respectively of clover or oats. Typically, the larvae are preferably found between 8 and 16 cm in height.

T. circumcincta is the only one to be able to overcome the winter together with O. ostertagi. 60% of T. circumcincta larvae survive for 16 weeks at temperatures between 4° and 16 °C, at -10°C they survive for 3 weeks, while they do not resist on pastures in the driest periods (July-August). Gastrointestinal nematodes are all characterized by a very small period of prepatent (time between the infestation and the formation of the adult able to reproduce), and eggs produced by the parasite appear early in the faeces of the host. This period is between 15-21 days for Cooperia sp., Haemonchus sp. and Teladorsagia sp. In addition, they are able to live in the host for several months, up to over a year.

Effects of gastrointestinal nematode infestation on the host

GINs are mostly responsible for reducing production performances, but these parasites can also cause mortality (Photos 2 and 3). Losses in milk production vary between 2.5% and 18.5% depending on the breeding context. In parallel with a decrease in production understood as less milk produced during lactation and, more in the longer term, a substantial deterioration in the compositional characteristics of milk was also showed throughout the production career, noting a decrease in the content of fat (29.9%), protein (23.3%) and lactose (19.6%). Such losses are usually observed in situations of subclinical parasitism. The general pathogenic mechanism in situations of subclinical parasitism can easily be assimilated to that of a nutritional disorder, since the action of parasitic helminths is manifested through a decrease in the ingestion of dry matter, a decrease in digestive efficiency, and a deviation of food nutrients from the functions of production and homeostasis to the repair of tissue damage and the elaboration of defensive responses.

Parasitism and goat farming

The impact of gastrointestinal parasitism in the goat within the livestock system of Occidental countries is essentially attributable to two factors, namely the widespread practice of grazing flocks and the peculiar characteristics of resistance/resilience of the goat species to parasitic infestation.

The degree of parasitism is also related to the amount of infesting larvae ingested together with fodder and depends on the eating habits of the goats; when goats have the opportunity to feed on plants and shrubs, less favourable for taking larvae than pastures, they are less parasitized than sheep. Unfortunately, grazing goats have both browser and grazer behaviour and then are widely exposed to GIN infestations.

In goats the degree of GIN infestation may vary depending on the breed; Angora goats appear more exposed to GIN infestations than other breeds precisely because of the poor aptitude for using shrubs. Recent Italian studies have shown that the autochthonous goat Nera di Verzasca, shows a lower degree of parasitism than Camosciata goats raised under the same conditions.

The degree of parasitism would also seem related to the production capacity: the best milk-producing goats, both in natural and experimental conditions, have the highest level of parasitism. Finally, goats at the first lactation can eliminate more eggs than other female animals; this varies, however, from one situation to another, in relation first of all to the type of farm management, which may differ between primiparous goats and adult ones.

As regards the characteristics of the response to parasitic pressure, goats and especially individuals with high genetic and production potential, have a lower capacity than sheep and cattle to develop over the years an adequate immune response to helminth reinfestations, including GINs; as a result, adult goats can eliminate eggs in greater quantities than sheep of the same age. This phenomenon becomes apparent when the two species are raised under the same conditions.

Photo 8: Posterior end of an adult male of Teladorsagia circumcincta; nematode that is localized in the goat’s abomasum

Photo 9: Posterior end of an adult male specimen of Trichostrongylus vitrinus; nematode that is localized in the small intestine of the goat