Italy more law observant than Denmark and Finland? Spain more compliant than Germany? You hardly hear this in the news, but these are the surprising patterns of noncompliance with the regulation on state aid in the European Union between 2000 and 2012. We report the results from a research conducted by Fabio Franchino and Marco Mainenti that explains how electoral institutions shape the incentives of governments to comply with international obligations.

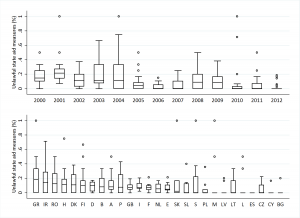

Check out this figure.

It illustrates the proportion of unlawful measures out of the total number of state aid measures adopted by the countries of the European Union (EU) (measures are unlawful if they do not comply with the EU provisions on state aid). Existing explanations of compliance and implementation in the European Union cannot satisfactorily describe these patterns.

These data not only display surprising patterns across countries but the simple fact that a government decides in the first place to avoid these rules is puzzling since the likelihood of being detected is high and the costs associated with noncompliance are not trivial (an unlawful aid must be recovered, including the accrued payable interests). Notice that certain state aid measures are compatible with EU law.

To explain why countries are willing to take these risks, we use the recent literature on how compliance with international obligations is affected by the types of electoral institutions employed in a country. These institutions can shape the incentives of governments to comply because of the misalignment they may engender between the collective objectives of a government party and the individual objectives of its members in the legislature.

We find that an increase of district magnitude improves compliance (district magnitude is the number of seats available in an electoral district). The higher the magnitude the less politicians are pressured to cater to constituency-specific interests and the less likely they will press their government to circumvent the EU provisions on state aid.

However, where either party leaders have no control over the ballot rank or other electoral rules strengthen the incentives to search for a personal vote, compliance decreases with higher magnitude. These electoral rules increase competition among candidates in a multi-member district. The higher the number of candidates, the toughest the competition and the need for politicians to distinguish themselves from copartisans, the higher the pressure to evade the rules.

Our work also provides evidence for the effects of electoral reforms on compliance.

The article is available here

Franchino, Fabio, and Marco Mainenti. “The Electoral Foundations to Noncompliance: Addressing the Puzzle of Unlawful State Aid in the European Union.” Journal of Public Policy 36, no. 3 (September 2016): 407–436. doi:10.1017/S0143814X15000343.

Data download (coming soon)

Personal websites: Fabio Franchino, Marco Mainenti